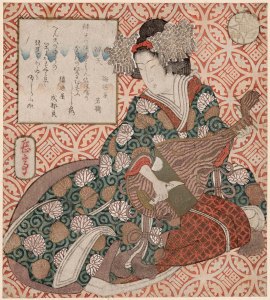

A Courtesan as the Goddess Benzaiten-sama

If you Google “Benzaiten” you will likely find her defined as the Japanese goddess of love. There are valid reasons for this, but in the West, these reasons are usually overlooked in favor of her most famous legend, in which a dragon falls in love with her and proposes marriage. However, this is arguably the last story one should use to justify Benzaiten-sama’s title as a goddess of romantic love.

In fact, the version of the dragon-taming myth most cited by popular mythology books is deeply and irrevocably tainted by sexist Victorian notions of a woman’s proper role. It was F. Hadland Davis and Lafcadio Hearn who first related the story of Benzaiten-sama subduing the dragon on Enoshima, in their books Myths and Legends of Japan and Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan.

As Davis and Hearn told it, the dragon was a child-eating monster that Benzaiten-sama tamed by agreeing to marry. Unfortunately, this recounting actually bears little resemblance to the Japanese myth, in which the dragon was an elemental force that flooded the entire East of Japan. He was not a fairytale dragon, a mere serpentine beast eating the village’s children. He was a frankly godlike entity that no iron-clad knight could hope to take down.

Furthermore, in the Japanese original, Benzaiten and the dragon do not even marry! In fact, the tale’s climax is the goddess’s righteously indignant refusal of the dragon’s proposal, on the grounds of his great wickedness. After her rebuke, the dragon repents and turns into a hill; in this form, he protects the children of Enoshima to this day.

According to Hadland Davis though, Benzaiten: “married the dragon, and was thus able, through her good influence, to put an end to the slaughter of little children.” (Davis, Myths and Legends of Japan. New York:Dover Publications, 1992. 207) Davis cites Hearn for this telling, but it is clear from reading any of the other tales in his Myths and Legends (originally published in 1913) that the author suffered from a bad case of leftover Victorian sentimentality.

This Victorian sentimentality should not be dismissed as harmless. The statement that Benzaiten-sama tamed the dragon “through her good influence” is thoroughly reflective of one of the most poisonous Victorian attitudes toward women, the idea that women are either Madonnas or Whores, to be either adored or abused.

In Davis’s telling, Benzaiten is a Madonna, who tames a rapacious beast with her “good influence” just as any Victorian housewife was supposed to deal with the brutishness of her husband through angelic tenderness.

Yet according to the monk Kokei, who first recorded the legend of Enoshima in 1047, Benzaiten-sama was possessed of “exquisite, brilliant charms” These charms are implicitly understood to be physical, as “Upon seeing the charms of the heavenly goddess” the dragon is smitten, and rushes to the island to “tell her of his deepest desire.”

Benzaiten did indeed tame the dragon, but in a way that would likely have baffled men such as Davis and Hearn. The Victorian notion of female sexuality as dangerous led to the dichotomy of Madonna and whore, and indeed, in later Japanese history a similar stigmatization of female sexuality would take place.

The Legend of Enoshima is not from that time.